Piccadilly Circus is one of the world’s most famous road junctions and known for it’s advertising lights that have been there for over one hundred years. For the longest time since world war two when they were the iconic lights have been turned off. The renovations will continue until the autumn when a brand new sophisticated single screen will be unveiled.

Piccadilly by Night, London (1965) by Elmar Ludwig

The name ‘Piccadilly’ came from the word ‘Picadils’ or ‘Pickadils’, which were stiff collars with scalloped edges and a broad lace or perforated border. At the beginning of the 17th century they were particularly fashionable. A man called Robert Baker made a lot of them and made his fortune. He bought land around the area we now know as Piccadilly and his house became known as Pikadilly Hall. He bought more land, with the help of money from a second marriage; and a map published in 1658 by Faithorne, the engraver, described the street as ‘the way from Knightsbridge to Piccadilly Hall’. Which is what Piccadilly, essentially, is today.

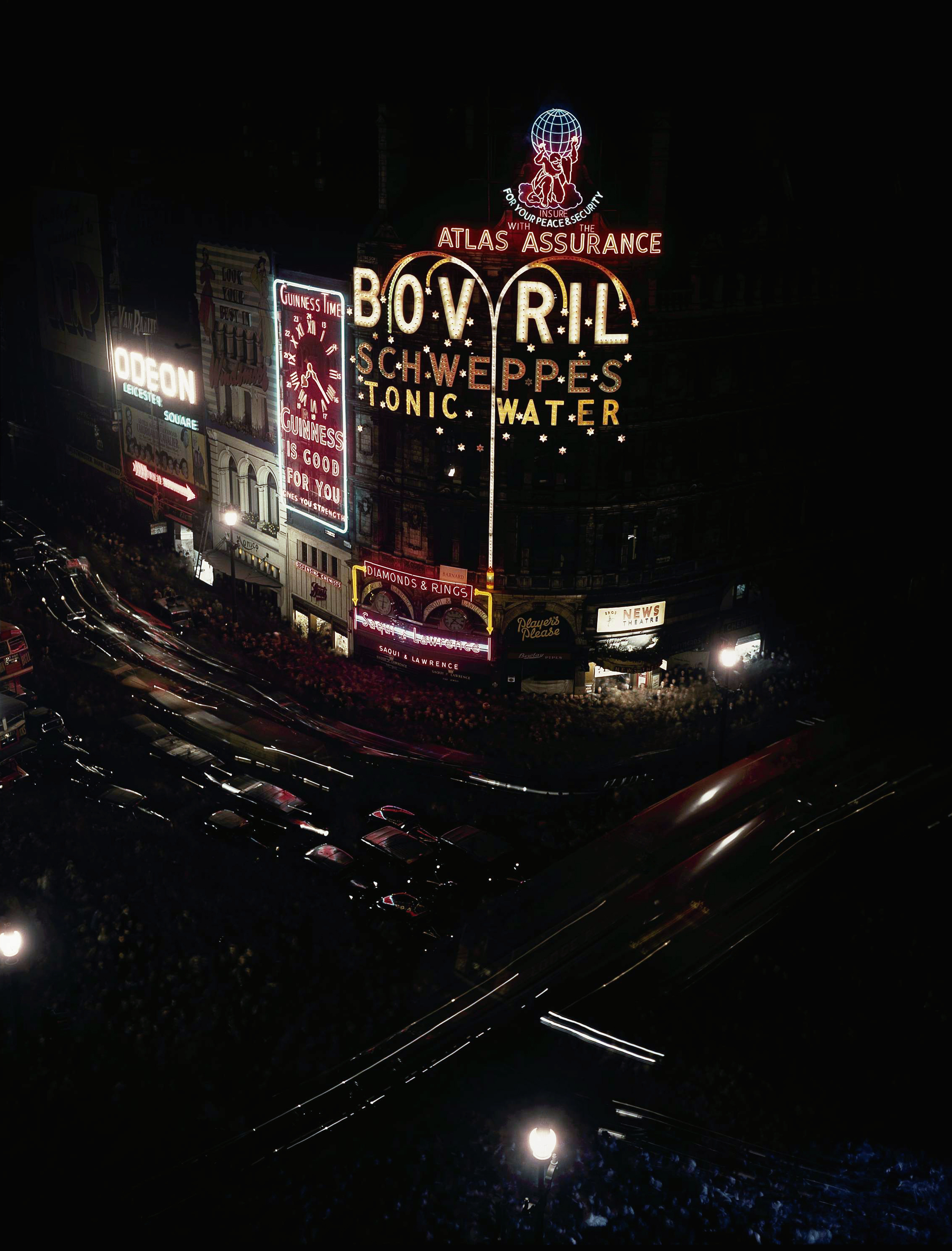

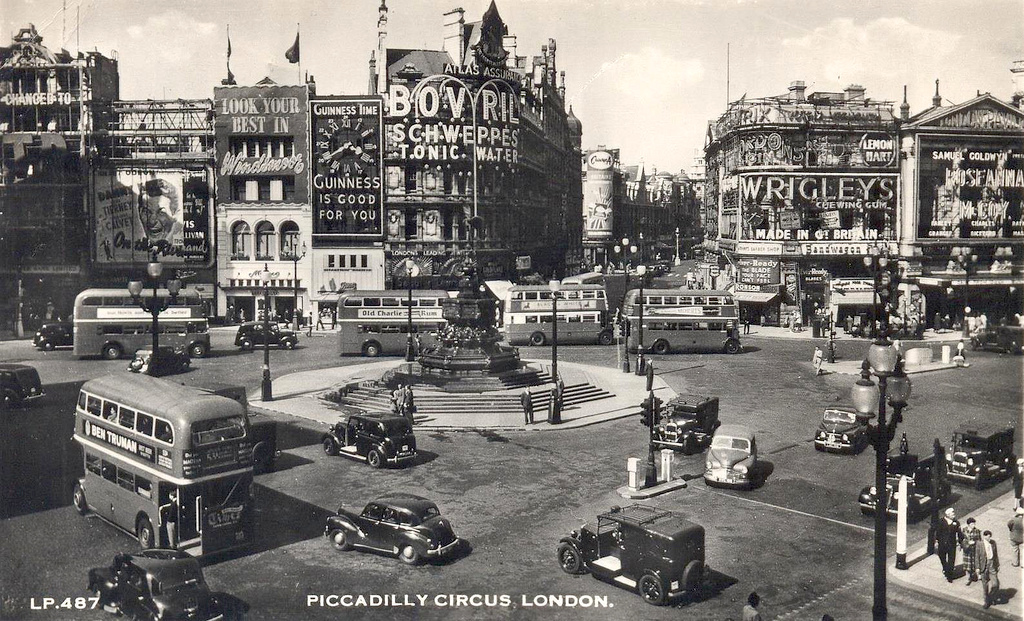

Piccadilly Circus in 1953 by Robert Capa

Sir Alfred Gilbert, who sculpted the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain, commonly known as Eros, and less commonly known to be made out of aluminium, ironically had no liking for Piccadilly Circus at all. In 1893 he described the Circus as ‘a distorted isochronal triangle, square to nothing of its surroundings—an impossible site, in short, upon which to place any outcome of the human brain, except possibly an underground lavatory!’

Piccadilly Circus in 1908

Plans had been made after the death of King Edward VII in 1910 to clear the area and create a rectangular open space with an adjacent Shakespeare Memorial Theatre and a National Opera House. The First World War came along, as did the Second, and the asymmetrical chaos that made up Piccadilly Circus remained … until 1954 that is.

Postcard of Piccadilly Circus and Shaftesbury Avenue 1911

In 1954 Coca Cola starting advertising at the famous London landmark and has done so ever since; but, more importantly, the property developer Jack Cotton bought the Monico site (named after the Cafe Monico that had been there since 1877) on the north side of Piccadilly Circus. His plans for a huge office block at Piccadilly Circus passed almost unhindered and unnoticed through the various planning stages – many newspapers reported on it at the time as if the redevelopment was a fait accompli. As soon as the plans were released, however, there was a public outcry with most Londoners wanting Piccadilly to remain exactly how it was. The Conservative government, however, asked for proposals for a grand integrated rebuilding plan that covered not only Piccadilly Circus, but also much of the surrounding area. They were particularly worried about the expected future growth of traffic.

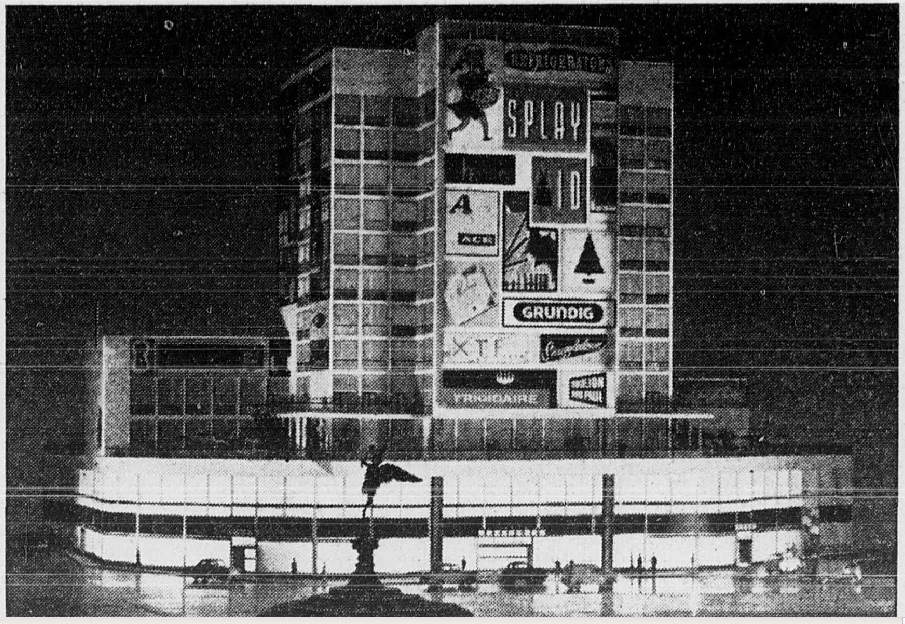

Piccadilly Circus tower block 1959 – this was an illustration of plans drawn up in the late 1950s to replace Piccadilly Circus as we know it now.

ord Holford, acting for the Greater London Council and Westminster Council, proposed a ‘double-decker’ scheme that segregated pedestrians on elevated concrete concourses sixty feet above the ground while several lanes of traffic roared past below. There was also to be a ring of office towers which would be overshadowed by a 132 m tower block on the Criterion Theatre site to the south of the Circus. This plan, with minor changes here and there, was kept alive throughout the rest of the sixties. It is mentioned in the short documentary film ‘Goodbye, Piccadilly’, produced by the Rank Organisation in 1967 as part of their Look at Life series, when it was seriously expected that Holford’s recommendations would still be acted upon.

Bobbies in London Piccadilly Circus 1966 by Michael Rogge

There was yet another scheme, put forward in 1972, that consisted of three octagonal towers, the highest of which was to be 73 m tall, to replace the Trocadero, the Criterion and the ‘Monico’ buildings. That year, with the wholesale destruction of Piccadilly Circus more than still on the cards, Hugh Cubitt, Westminster Council’s planning chairman, let it be known that he hoped the scheme could be started as soon as possible, so as to combat the decay of what he called: ‘little more than a down-at-heel, neon-lit slum.’ [18]Most Londoners thought, ‘yes but it’s our down-at-heel, neon-lit slum and we’d like to keep it that way, thank you!’ A year later the Observer wrote: ‘Piccadilly Circus, more than anywhere else in the country, is a place for the people. It is not, first of all, a traffic junction nor an office centre. It is somewhere people go to wander about, gawp and gossip, and generally amuse themselves. Those who have drawn up successive plans for its redevelopment have failed to understand its real nature, and, one after the other their efforts have been laughed to scorn.’

Piccadilly Circus in 1959 by Graham Knott.

In May 1979, after almost eighty years of different redevelopment plans of Piccadilly Circus, the latest plans were unveiled. At last, all the grand projects featuring massive office blocks and ‘pedestrian walkways in the sky’ were rejected in favour of what Mr ‘Sandy’ Sandford, chairman of GLC’s central area planning committee begrudgingly called the ‘least change’ plan. Essentially, except for some pedestrianisation on the south side, it meant that it was to remain roughly how it had always looked, and what we see at Piccadilly Circus today.

Coventry Street looking up to Piccadilly Circus Allan Hailston April 1956.

“Always, from the first time he went there to see Eros and the lights, that circus have a magnet for him, that circus represent life, that circus is the beginning and the ending of the world. Every time he go there, he have the same feeling like when he see it the first night, drink coca-cola, any time is guinness time, bovril and the fireworks, a million flashing lights, gay laughter, the wide doors of theatres, the huge posters, everready batteries, rich people going into tall hotels, people going to the theatre, people sitting and standing and walking and talking and laughing and buses and cars and Galahad Esquire, in all this, standing there in the big city, in London. Oh Lord.”― Sam Selvon, The Lonely Londoners

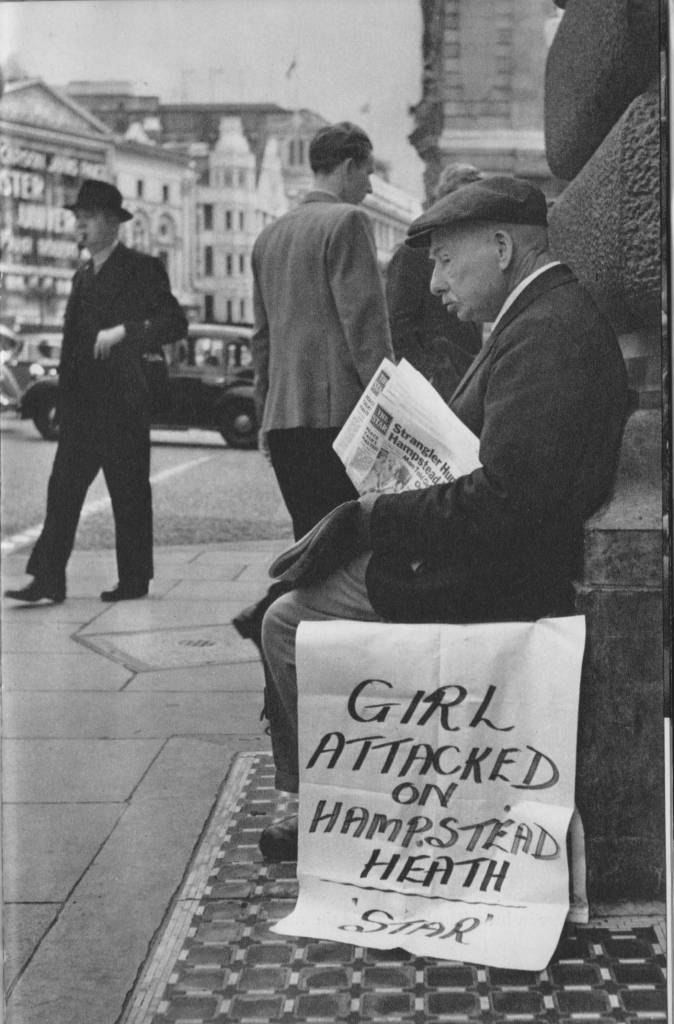

George Tippins newspaper seller Piccadilly 1955, by Cas Oorthuys.

“My Dad says that being a Londoner has nothing to do with where you’re born. He says that there are people who get off a jumbo jet at Heathrow, go through immigration waving any kind of passport, hop on the tube and by the time the train’s pulled into Piccadilly Circus they’ve become a Londoner.”― Ben Aaronovitch, Moon Over Soho

Hannes Kilian – Piccadilly, London, 1955.

“As I lounged in the Park, or strolled down Piccadilly, I used to look at everyone who passed me, and wonder, with mad curiosity, what sort of lives they led. some of them fascinated me. Others filled me with terror.”Oscar Wilde

After nearly 10 years of comparative gloom, the bright lights of Piccadilly Circus come back to London, April 2, 1949, when the ban on the use of electricity for outdoor advertising was lifted at noon. This is the scene as crowds watched the signs light up again. The ban will be re-imposed on October 2.

Piccadilly Kodachrome Chalmers Butterfield 1949

Piccadilly Circus 1949.

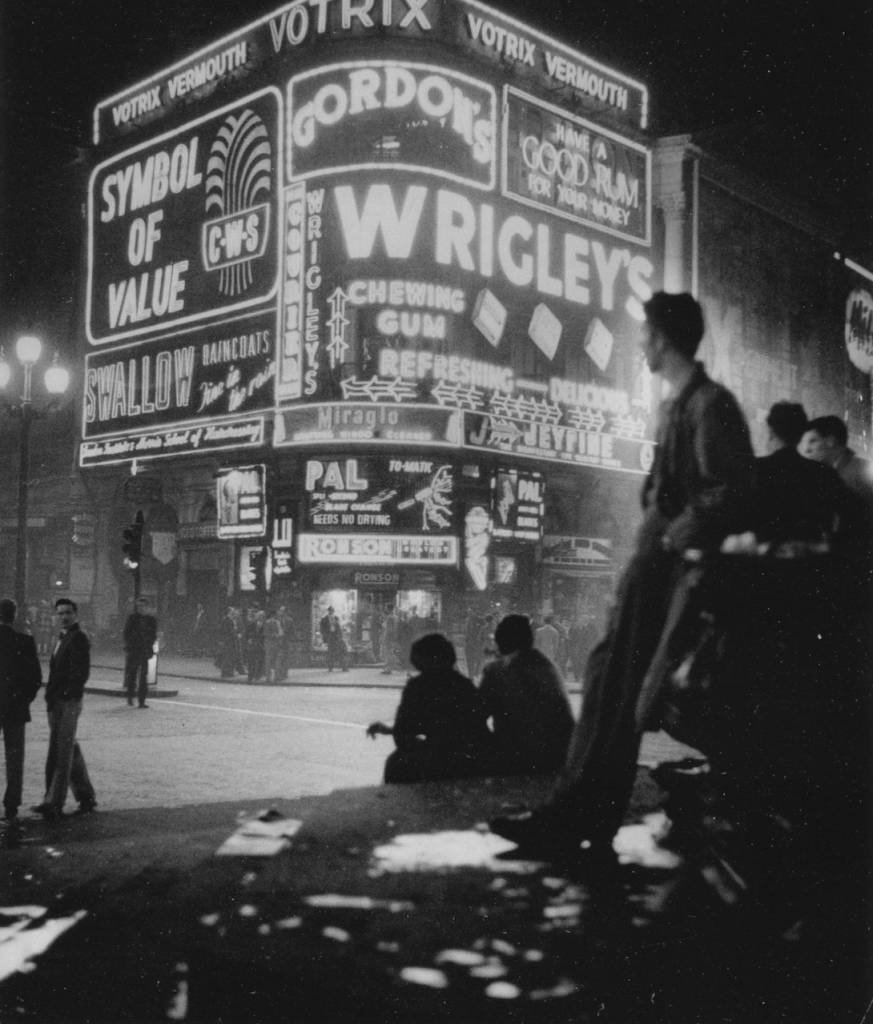

Piccadilly Circus in 1955, photo by Cas Oorthuys

Piccadilly Circus in 1960 Harold Slatore.

Piccadilly Circus in 1961.

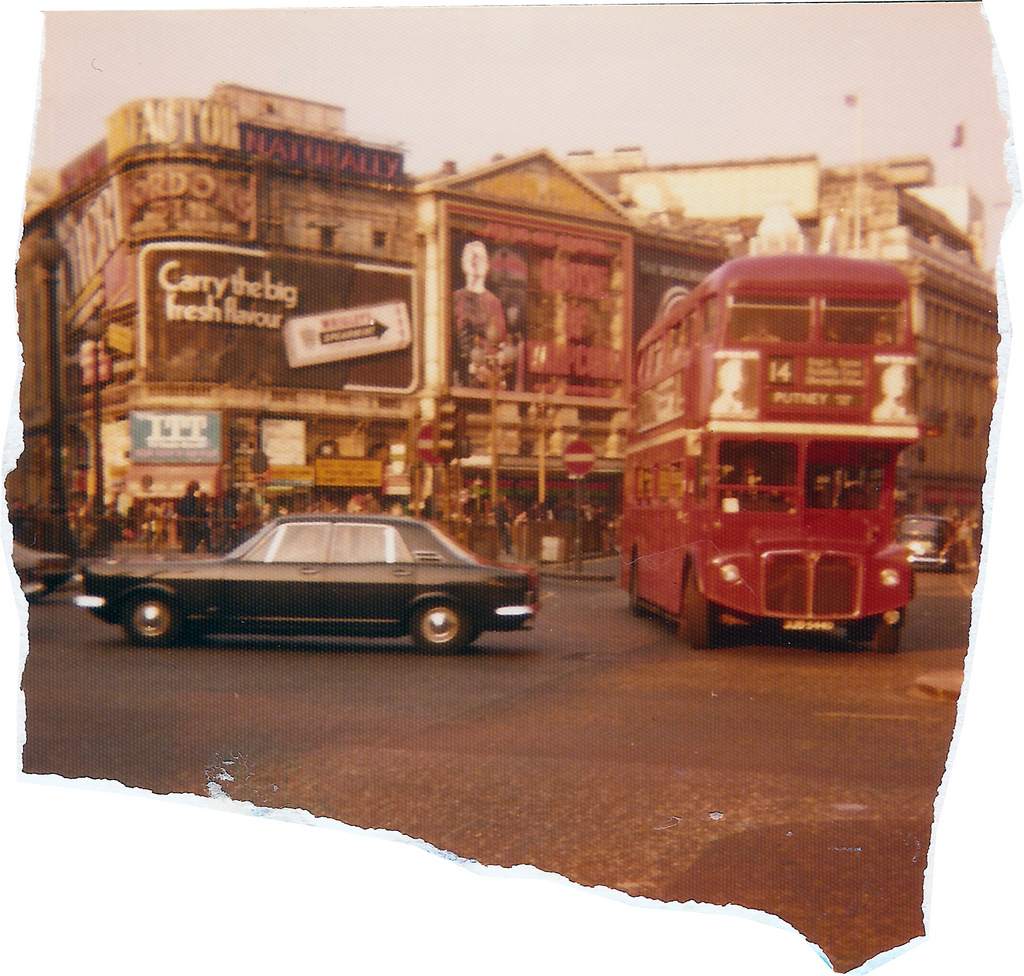

Piccadilly in 1968

Piccadilly in 1970.

Piccadilly Circus, 1974 by Daniel Vaulot

Piccadilly advertising in 1969 by Bernd Loos.

Piccadilly and Regent Street area of London in 1953. By Aerofilms Ltd

Piccadilly April 2, 1949 photo Eddie Worth

Piccadilly at night in 1969. Photo by Bernd Loos

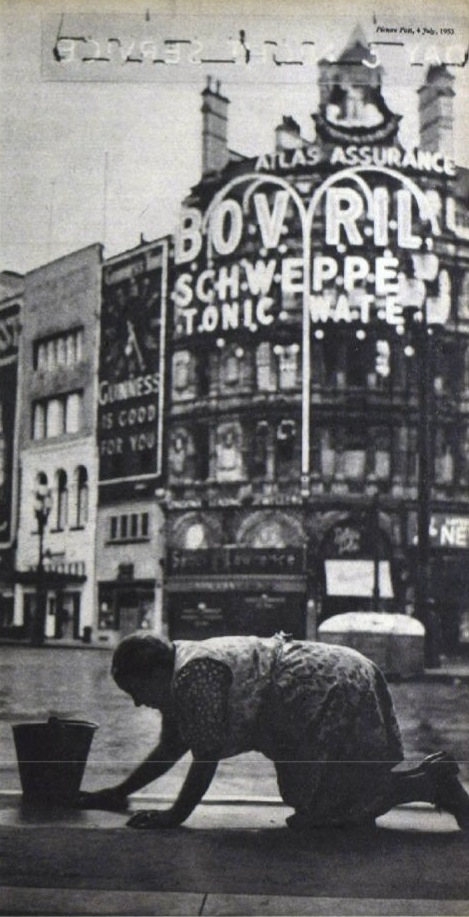

Piccadilly by Bert Hardy 1953

Piccadilly c.1960

Piccadilly Circus 6th Dec 1952

Piccadilly Circus 1949 unknown photographer

Piccadilly Circus 1961 CW Cushman

Piccadilly Circus in 1965

Piccadilly Circus 1967/68

Piccadilly Circus 1968

Piccadilly Circus, 1970 by Harold Slatore

Piccadilly Circus in 1973

Piccadilly Circus 1974 Peter Krumme

Piccadilly Circus by Hans Richard Griebe

PICCADILLY CIRCUS ELECTION RESULTS 1951

Piccadilly Circus Last Tube home 1955

Piccadilly Circus Man of La Mancha RB Reed 1968.

Piccadilly Circus Photochrom c.1895

Piccadilly Circus postcard 1951

After being postponed for 24 hours owing to bad weather conditions, London’s big black out took place last night, and it was observed not only in London but over the whole of south-east England and the midlands lights wert all extinguished, cars only being allowed to proceed with their dim side lights burning complete darkness reigned everywhere with only one or two receptions where the timing. Apparatus of street lamps had some wrong and with searched lights stabbing into the night sky as their exercises proceeded overhead, the scene was vividly reminiscent of an air raid during the last war. A view of a night, before the great black-out began in London August 10, 1939.

Piccadilly Circus in 1974

Piccadilly night shot on the 38 1952/3

Piccadilly postcard 1972

Piccadilly Postcard by D. Noble – John Hinde studio, 1975

Piccadilly routemaster 1974 Karl-Heinz Lilienthal